Fuji Music: When Drums Learn to Speak

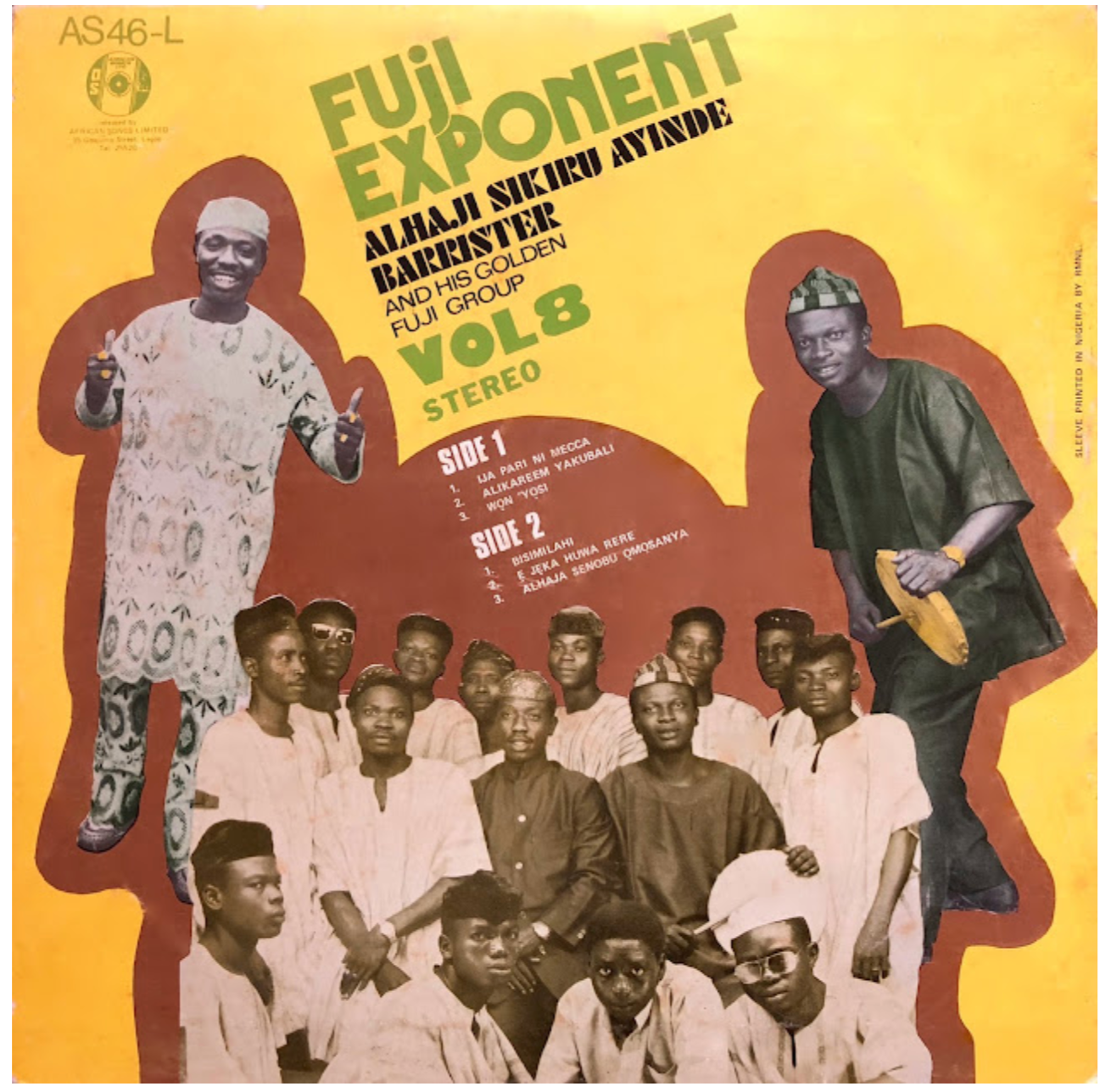

“Fuji Exponent Vol. 8” alternate cover - African Songs Ltd (via Discogs).

How Ramadan devotion became Nigeria's percussive revolution

The talking drum does exactly what its name promises. The dùndún, as it's called in Yoruba, has two heads connected by leather cords. Squeeze them and the pitch rises, following the tonal patterns of speech. Relax your grip and it drops low. In the hands of a master, this hourglass-shaped instrument doesn't accompany language. It becomes it.

This is where Fuji music begins. During Ramadan in southwestern Nigeria, Muslim communities needed waking before dawn for suhoor, the meal before fasting. Young men would walk the streets with drums, performing what they called wéré music, or ajísari ("waking up for sari"). The drums spoke prayers, recited Quranic verses, praised Allah. Cities like Ibadan would pulse with rhythm before sunrise. A percussive alarm clock that doubled as devotion.

By the 1950s, a young boy named Sikiru Ayinde was already winning competitions with his wéré performances. At ten years old, he had a gift. He'd infuse traditional calls with his own Quranic recitations, add harmonica between drum sequences, bend the form just enough to make it his. The elders called him Alhaji Agba. His friends called him Barry Wonder. History would call him Barrister.

The Airport Poster

Barrister had a problem. Wéré only existed during Ramadan. How do you build a career around seasonal devotional music?

He started experimenting. Blending sákárà rhythms with apala grooves, introducing flutes, pushing the tempo faster. By the early 1960s, he'd created something new. He just needed a name.

Standing in an airport one day, Barrister saw a poster advertising Mount Fuji, Japan's highest peak. Something about it struck him. Volcanic, powerful, impossible to ignore. He borrowed the name. The genre became Fuji. No connection to Japan, no volcanic metaphors in the music itself. Just a word that sounded right, felt modern, carried mystique.

The Yoruba words people sometimes confuse it with tell their own stories: fúja means "to flee." Fáájì means "enjoyment" or "leisure." Fuji somehow contains both impulses.

Percussion as Philosophy

Talking drum performers in Lagos - Lagos State cultural archives (photographer unlisted).

Walk into a Fuji performance and it's wall-to-wall drums. The ensemble surrounds you. Multiple dùndún in different sizes, the deep-voiced gbedu, the sharp snap of bata drums, shekere rattles adding texture. No guitars here. The rhythm section is the entire band.

The lead singer doesn't perform over this polyrhythmic foundation so much as engage in dialogue with it. Call and response unfolds between vocalist and chorus, but also between voice and drum, drum and drum. The talking drums reply to the singer's phrases, comment on them, extend them. Conversations happen at multiple levels simultaneously.

Barrister sang in an Arabic melismatic style, his voice ornamented and fluid. The lyrics moved between Yoruba and Islamic prayer, between praise songs for patrons and social commentary, between the spiritual and the scandalously worldly. A Fuji performance could last hours. The tempo building, the crowd dancing, the drums never stopping.

Kings and Rivalries

By the mid-1980s, Fuji had exploded. Lagos and Ibadan became battlegrounds for competing styles, different schools of rhythm, feuding maestros claiming supremacy. These weren't subtle artistic disagreements. Fuji fans were fanatics. Concerts could turn violent. Sound system clashes, Lagos style.

Kollington Ayinla brought speed and aggression. His hit "Ijo Yoyo" pushed tempos until the drums blurred. Barrister remained the godfather, constantly innovating, recording over 140 albums across his career. Then came the protégé.

Wasiu Ayinde had grown up around Barrister, literally. Packing instruments for the band as a teenager, learning the craft from the inside. By the time he released "The Ultimate" in 1993, he had his own vision. K1 De Ultimate, as he became known, made Fuji appeal to younger, more cosmopolitan audiences. That same year, he was crowned King of Fuji at NTA Ibadan. Barrister himself passed him the ceremonial cap on stage. The throne had changed hands.

Others carved their own territories. Pasuma brought street credibility and hip-hop collaborations. His 1995 album "Orobokibo" became so huge it permanently added the word "orobo" to Nigerian slang. Saheed Osupa positioned himself as the intellectual, filling his tracks with proverbs and political philosophy. Obesere went provocative with his "Asakasa" style, designed to scandalize parents and thrill their children.

These weren't just musical differences. They were competing visions of what Fuji could be, who it belonged to, where it should go.

The Political Drum

Nigeria in the 1970s: civil war, oil boom, military coups, dictatorships rotating through power. Fuji musicians, rooted in working-class Muslim communities, became unexpected political voices. Their audiences were everywhere. Weddings, festivals, street corners, elite parties. Everyone heard what they said.

Barrister's politics evolved with the times. In 1983, he preached against corrupt democratic leadership. In 1984, he cautiously welcomed military intervention. By the 1990s, facing down Sani Abacha's brutal dictatorship, he was protesting openly. The drums spoke not just Yoruba now, but resistance.

Fuji carried messages other genres couldn't. Its Islamic roots gave it cover. Its working-class base gave it legitimacy. Its percussive complexity made it nearly impossible to suppress. How do you censor a talking drum?

Women at the Margins

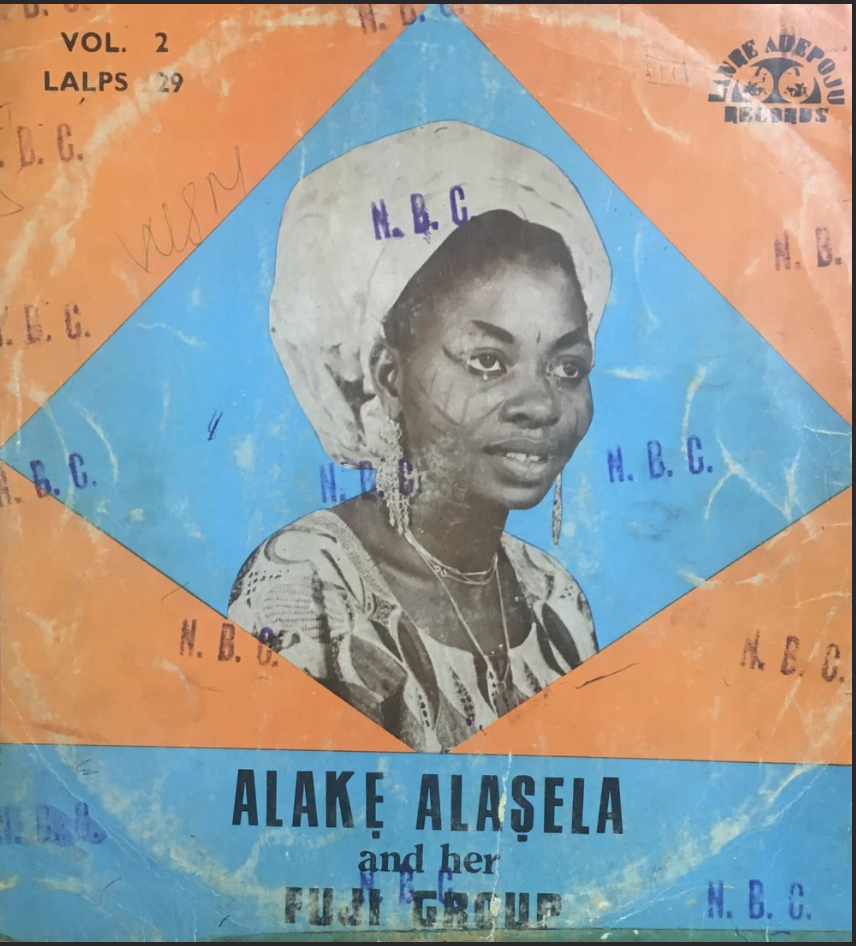

Alake Alasela album cover - Lanre Adepoju Records (via Discogs).

The women who played Islamic wákà, sister genre to Fuji, rarely get mentioned in the standard histories. But they were there from the beginning. Performing at weddings, welcoming pilgrims home from Mecca, creating their own percussive devotional music.

By the 1980s, professional women vocalists were fronting their own bands, playing the same circuits as their male counterparts. The music looked similar on the surface. Same instruments, same tonal languages, same spiritual roots. But wákà developed its own aesthetics, its own rhythmic signatures. Alhaja Batuli Alake and later Salawa Abeni became legends in their own right.

Fuji histories tend to focus on the male maestros, their rivalries, their innovations. The women kept playing anyway, building parallel traditions that deserve their own essays, their own documentaries, their own archived footage.

Fuji Now

Listen to contemporary Afrobeats and you'll hear Fuji everywhere. That percussive density, those rapid-fire rhythms, the way Nigerian producers layer talking drums under synthesizers. All of it traces back to those pre-dawn Ramadan performances in 1950s Ibadan.

Burna Boy name-checks Saheed Osupa as a major influence. Asake builds entire tracks around Fuji-derived rhythms. The genre has spawned offshoots: classical fuji, neo fuji, fujipiano, fuji-fusion. Each generation remixes the formula, adds new elements, claims innovation while honoring lineage.

In February 2024, professor and filmmaker Saheed Aderinto released "The Fuji Documentary: Mr. Fuji: Barry Wonder." The film chronicles Barrister's life, drawing international attention to a genre many younger Nigerians take for granted. It's been screening at universities and film festivals worldwide, asking audiences to hear Fuji differently. Not as nostalgia, but as living history.

Fuji fuses Islamic philosophy with Yoruba poetry, spiritual devotion with secular celebration, traditional percussion with constant evolution. It speaks across class lines, from political corridors to street corners. The talking drums keep talking, the rhythms keep mutating, the genre keeps refusing to stay in the past.

Somewhere in Lagos right now, a dùndún player is squeezing leather cords, making the drum rise and fall, matching the tones of Yoruba speech. The tradition continues. The drums still speak.